Fermented Vegetables is a big book of fermenting so big in fact that there was no room for a foreword. Cheesemaker and author Gianaclis Caldwell had graciously written one and it seemed on fair that we shared it here.

With out further ado we present the foreword by Gianaclis Caldwell

Cheesemaker, Pholia Farm Creamery, Rogue River, Oregon

Author: Mastering Artisan Cheesemaking, The Farmstead Creamery Advisor, The Small-Scale Dairy: The Complete Guide to Milk Production for the Home and Market, The Small-Scale Cheese Business: The Complete Guide to Running a Successful Farmstead Creamery

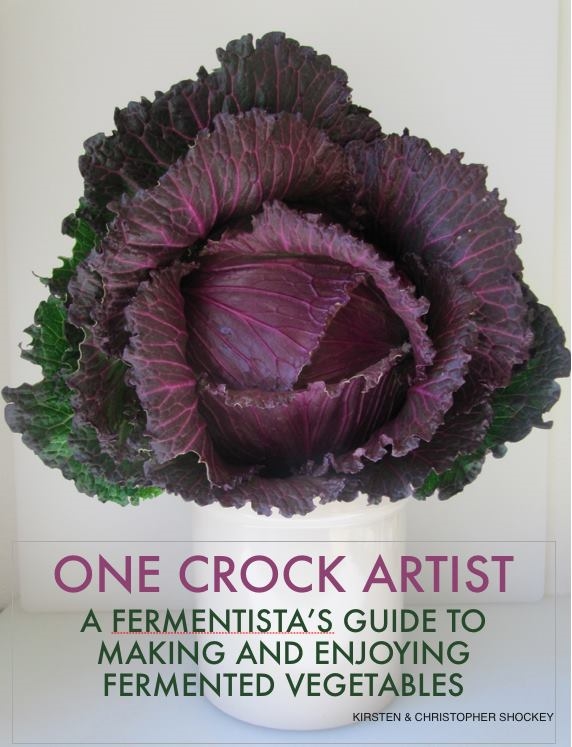

One of my childhood memories is of two enormous ceramic crocks sitting on the shelves of our big walk-in pantry. The first was filled with fermenting cabbage, the other with something a bit more mysterious and off limits “home-brew”, better known as beer. The pantry, which we called “the fruit room” as it held boxes of apples and pears from our orchard and neatly organized rows of mason jars filled with canned peaches, tomatoes, and the rest of the bounty from our huge organic garden, was a long, narrow room whose thick walls were insulated with sawdust meaning it would stay cool throughout the long, hot summer–the perfect place for fermenting foods. In those days I was not a fan of tangy, salty, or yeasty foods, so the big crocks, which now that I am grown do not seem quite so gigantic, held no appeal to me. But I can remember my mother and sister both enjoying the kraut straight from the crock and my sister sneaking dipperfuls of beer out of the amber depths of the homebrew crock—before my parents had the chance to get it into more easily inventoried bottles.

I didn’t really ponder or begin to appreciate the process of fermentation until fairly recently. Even my career as a cheesemaker, basically a professional milk fermentista, had not lifted the veil on the wide world of fermented foods. About five years ago, however, a previously little known product called kombucha started appearing on our local grocery store shelves. Fermented tea, kombucha seemed a very grown-up drink–not too sweet, refreshing, and to top it all off, actually good for you. About the same time, I picked up a copy of Sandor Katz’s popular book Wild Fermentation in which he not only told how to make this delicious (and rather high priced) brew, but he included an illustration of a kombucha “mother”. Also known as a “mushroom” or SCOBY, this bizarre looking, jelly-like, slightly disgusting thing is responsible for turning an otherwise sweet and rather boring beverage into the intriguing, complex drink. I had to have one.

Our part of Oregon is teeming with homestead and small farmers. The bounty of their acreage fills not only their own bellies, but also the farmers’ market and roadside stands. In one particular valley I had a couple of farming friends, one producing pasture raised pork and poultry and the other was building an on farm fermentation kitchen. If anyone would have a kombucha mother to spare, I figured it had to be the Shockeys. A visit to their farm not only yielded the sought after, gelatinous SCOBY, but also a revolutionary lunch at the family’s distinctive hardwood table. A pot of delicious soup and a bowl of fresh salad greens were accompanied by several jars of brightly colored and interesting smelling fermented vegetables. What is this, I thought. I watched as each tall, curly- haired member of the family topped their soup and salad with forkfuls of krauts and long green beans from the jars. I followed their lead and tentatively tasted. These fermented concoctions were not too salty or sour, like the kraut of my childhood, and they were filled with flavor! In response to my compliments, Kirsten espoused the health benefits and joy of fermenting vegetables.

I have had the great pleasure of seeing Kirsten and Christopher’s obvious knowledge and passion for fermentation transformed into this magnificent book on the subject. From sitting in a local café together while I worked on my own manuscripts, to finally having the privilege to write this foreword, it has been a joy to be a part of their process—especially since it has resulted in such scrumptious results! Indeed, I had difficulty writing a foreword that didn’t come across as a paid for advertisement…

There are several fermentation books, some, such as Sandor Katz’s original as well as his most recent, The Art of Fermentation, will be irreplaceable inspiration and reference books. But Fermented Vegetables will not only make you want to become a fermentista, it will virtually guarantee success. Thanks to the Shockey’s clear instructions, inspiring photography, pertinent science, and options for successfully performing each task–you will no doubt find yourself an accomplished fermentista before you can spell Lactobacillus.

Writing both as a couple and sharing their individual perspectives in engaging sidebars, Kirsten and Christopher use humor and tales of their own and other fermentista’s mishaps and revelations to encourage and inspire the reader’s development and intuition. Beginning with a simple, foundational recipe, the book leaves no excuses for procrastination. As you proceed through the book, the recipes range from basic to intricate, practical to sophisticated, and staples to indulgences. I have no doubt that my favorite recipe chapter is likely to be the fun and provocative (I mean really, healthy cocktails?) “Happy Hour” section. Their presentation of recipes by category of vegetable will solve many of the dilemmas facing those eating seasonally—either from the abundance of their own garden or from that of the local farmers market.

The kombucha mother that Kirsten handed to me that day several years ago continues to thrive–though now through daughters hundreds of generations removed from the original–and produce delicious, and nutritious, kombucha in a crock on our kitchen counter. Krauts and kimchis from local producers who barter for our cheeses occupy their own space in our refrigerator and their spicy and colorful contents are a part of many meals. My own vegetable fermentation has not yet extended beyond sour pickles, and I really felt little inspiration to do more, that is until now. While I will likely never use the big, five-gallon crocks that my mother did (she still has one) I do have two smaller versions that arrived under the Christmas tree last winter sitting empty. Hmm, maybe...