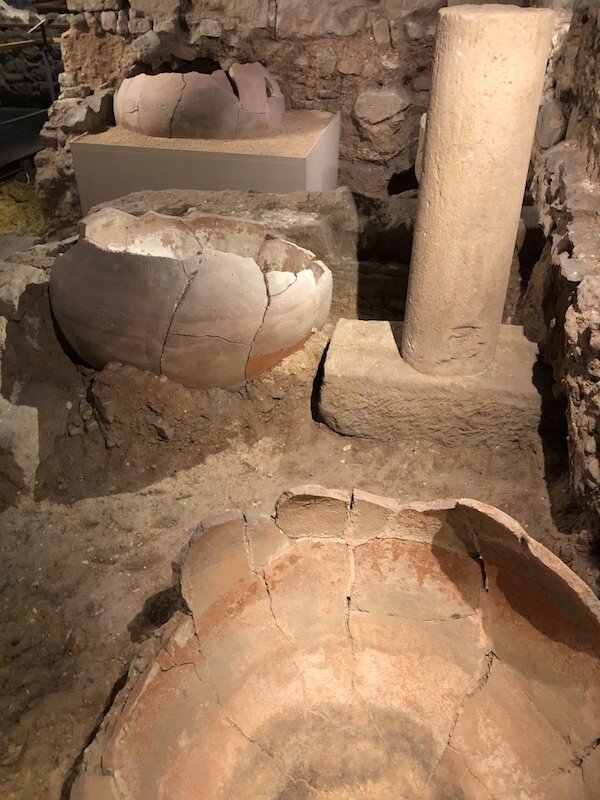

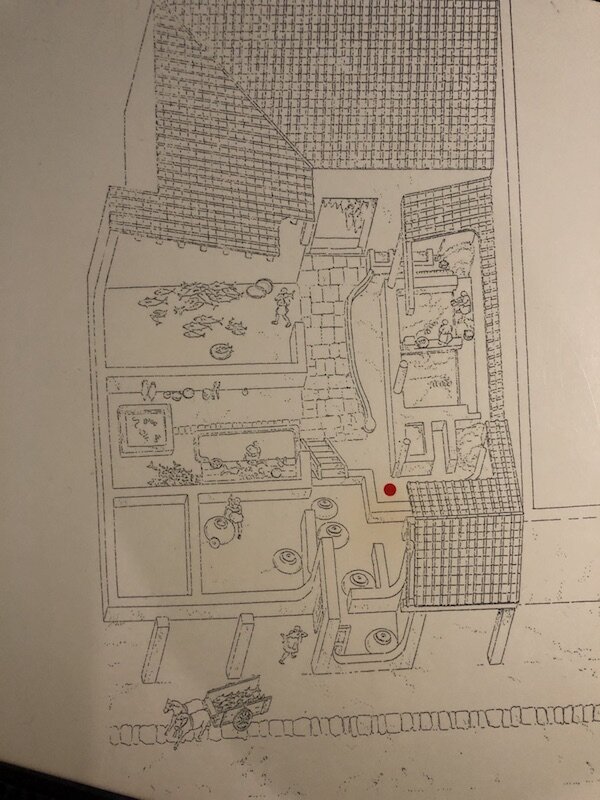

Here is a Garum recipe that is an extension of our previous post about Roman garum making in Barcino (modern Barcelona) ancient times. At its most basic garum (also sometimes called liquamen) is seafood, salt, and time. Roman makers though, we imagine, were looking for competitive edge and some shoppers for unique flavors. Of course, the choice of sea foods was paramount in flavor and likely ultimate price. We’ve read in numerous places mackerel made a good common garum, including Pliny. The best according to a 10th century book of agriculture the Geoponica was made with tuna innards, blood and gills (full utilization in action). However, the maker might include wine and herbs. One ancient recipe translation we read called for highly aromatic dried herbs that line the base of the fermentation vessel, then as fish and salt are layered so are more herbs. The Barcino “factory” was right next door to a winery so I can see a partnership with less than ideal wines going into the garum.

The following recipe is a traditional fish based garum if you are interested in a modern spin on this umami sauce you can learn to make a bone marrow garum here.

In our research recipes layered salt on the fish. The same Geoponica recipe is roughly 12.5% ratio (8 parts fish to 1 part salt) but we found the flavor crisper and cleaner at a 18% salt by weight of fish ratio. Ancient recipes used significantly more salt than most people do today. Remember, salt was the preserving mechanism and the fermentation control, and it wasn’t something people couldn’t get away from because it was hidden in processed foods. Garums and other preserved nutritionally dense foods where the processed foods and the way the fresh foods were salted.

Heat is also a consideration. The ancient recipes all call for some sunshine and our modern sensibilities know that enzyme action is faster and most efficient around 138°F/59°C. These are the temperatures we use to speed up koji-based ferments. Temperatures in different regions might also contribute to the varying times prescribed—from 20 days to 6 months.

2 pounds (900 grams) raw mackerel, or other raw fatty fish (sardines are another good choice)

5.7 ounces (162 grams) salt

Optional dried herbs

1. Chop the whole fish up, blood and guts and all.

2. Mix thoroughly with the salt and optional herbs. Everything should be coated.

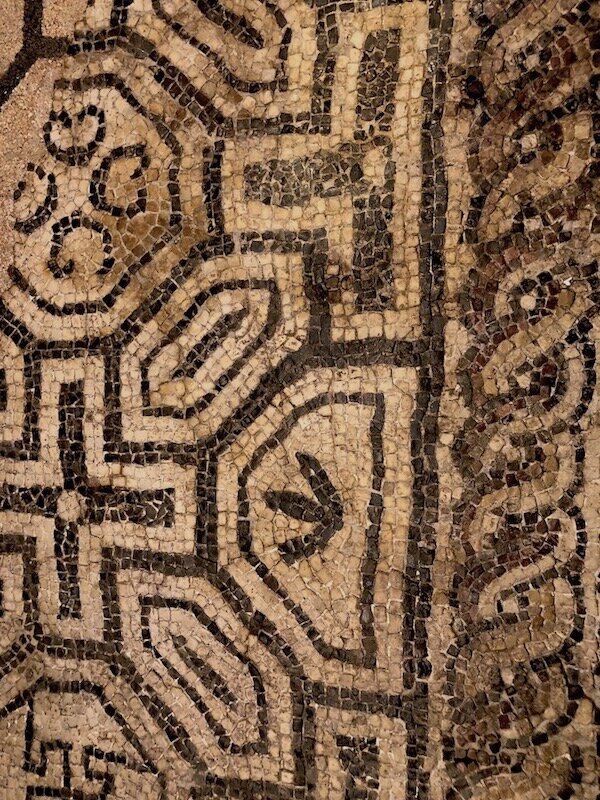

3. Place mixture in a fermentation vessel. If you have an amphora go for it, otherwise use a half-gallon or gallon glass jar. Lid finger tight.

4. Keep in sun, or warm, if possible. Warmth will move things along.

5. Stir daily for the first two weeks. The more you stir the better. If you want to increase the surface area which will help with the enzymatic break down, you can mix it with a hand blender if you want to.

6. Allow to ferment for about 4 months at room temperatures, stirring occasionally. It will go faster if you keep it warmer than that. The mixture will completely dissolve over time, if you don’t blend it you will still see the bones.

7. It will separate and the liquid will be a variation of a clear amber color.

8. Strain off the liquid. Use a coarse strainer first and then a fine strainer and finally a sanitized dense cheese cloth.

9. Bottle the liquid. It will last indefinitely.