If you don’t recognize the name Garum you might have tasted, or at least smelled, fish sauce from southeast Asia. Other names for garum fish sauces are liquamen, allec, or muria, but we suspect it is less likely you have come across those names. Two thousand years ago garum was very popular in the Roman Empire, having probably been introduced to the Roman palate after they conquered Carthage, across the Balearic Sea in what is now Tunisia. The fermented fish sauce garum was a staple for all levels of roman citizenry. Besides its concentrated umami punch it’s also an amazing way to preserve an ocean’s perishable abundance for a long period of time. The secret to its longevity is in the process, which you might find fascinating, impossible or just a little gross. More on that in a moment.

In 2019 we were invited to Spain to teach different fermentation techniques, including making miso, hard cider and fermented condiments. So, on our last day in Barcelona we decided to get away from fermentation for a few hours and walk across the city to the Gothic Quarter to find the Picasso Museum. Walking through the tight cobblestoned streets of this old part of Barcelona you can easily imagine a scene from the middle ages, or for Christopher something from Monty Python’s Holy Grail. It feels old, worn yet solid as the giant blocks of stone that make up many of the walls. Upon finding the museum we realized a lot of people had already had the same idea and it would be many hours before the next tickets were available. So we did what we usually do in new places and wandered around. That’s when we found something amazing completely by accident.

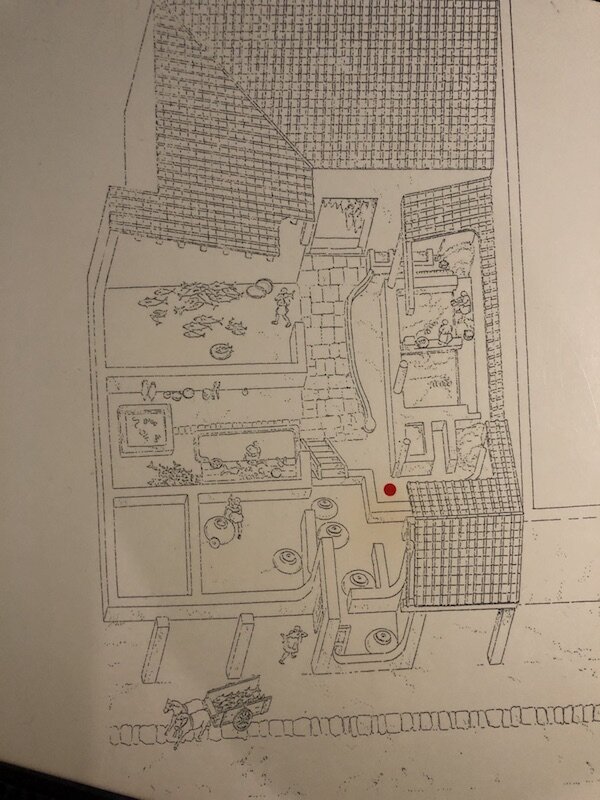

Just a few minutes’ walk down a couple of narrow streets we randomly walked into the yawning vastness of the Placa del Rei, a square surrounded by the Palau Reial Major or Grand Royal Palace. It was sunny and the square and massive spreading steps to one end were covered with couples and families taking in the sun’s rays or enjoying a small bite to eat. Kirsten noticed the simple sign and being the more adventurous one convinced Christopher his stomach could wait until they checked out this Museum of the History of Barcelona. We checked in our backpacks into lockers, grabbed English versions of the handheld audio tour wands and were escorted into an open elevator. Two floors down we stepped out into an underground Barcelona of 2000 years ago, the roman fortification of Barcino. Painstakingly excavated for more than 30 years below the palace above and featuring among other things the remains of a very old fermentation business it takes a few minutes for you to take in what your eyes are seeing. Elevated walkways above the ruins allow for you to basically hover a few feet above over 43,000 square feet of ruins, including a winery and a factory that produced a fermented fish sauce called Garum. (See the artist rendering in the slide show.)

Alright, remember the process, which you might find fascinating, impossible or a little gross? We are in the find-it-fascinating camp, but you be the judge. If you find yourself in the fascinating camp check out this recipe. To understand what is happening in garum fermentation you need a quick anatomy primer. Organisms have in their guts microbes that break down the foods ingested to supply themselves and their host with energy. This happens in halibut as well as in a human. These microbes stay within our guts, keeping their activity focused on what we eat and not on ourselves and the same goes for the fish these early Spanish fisherman were catching. However, if you chop the fish up and throw everything in a big vat with layers of salt, these microbes break down the proteins and fats of the fish, sea urchins and whatever ends up down in there to liquidy amino acids, fatty acids and the bones. It’s the animals’ own digestive juices turned upon themselves. Perhaps a cautionary tale to remember to feed your gut microbes within you well, otherwise, well…

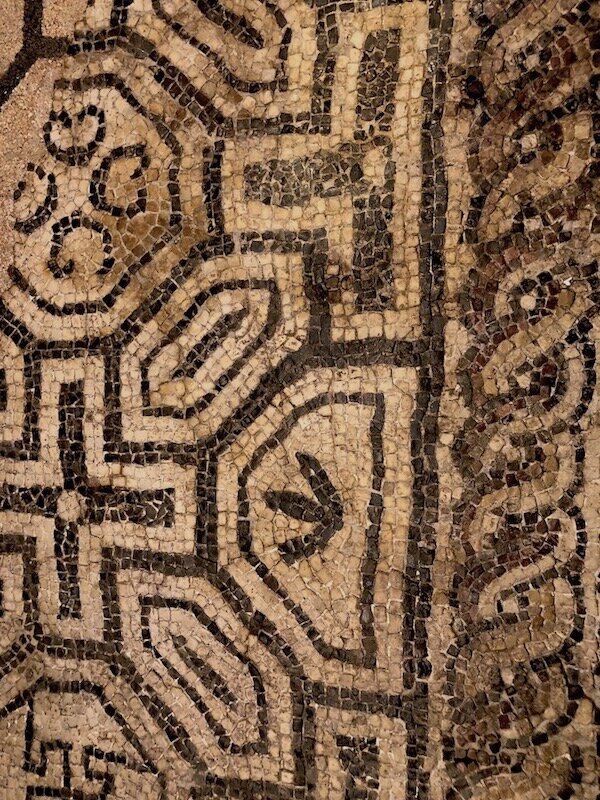

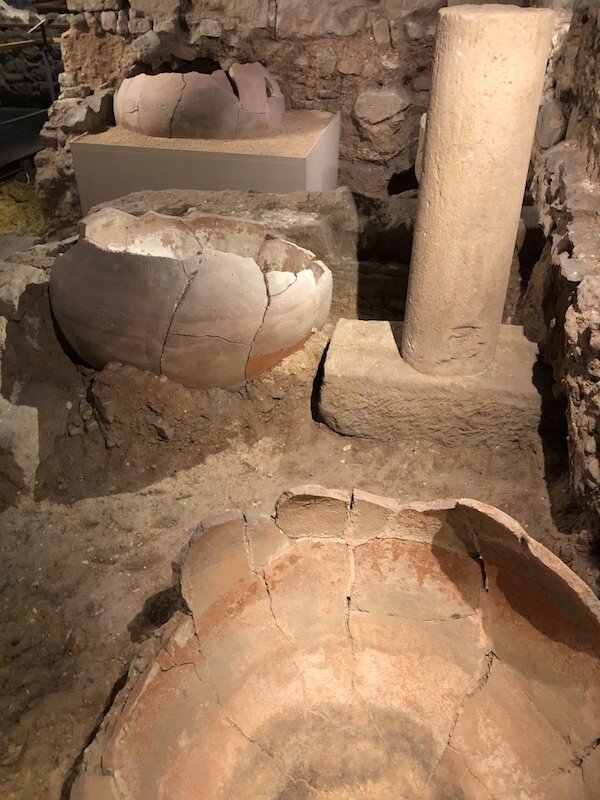

The initial salted stage set up the fermentation was in large vats cut out of the limestone and sheltered from the rain and sun by awnings of sorts. (See the rectangular stone tubs in the slide show.) After some time through a series of connected troughs and drains the fermented fish mash was transferred to smaller containers that would have been outside on the patio to further condense in the sun. Beside these were the well-preserved remains of mortars that were used when the finished garum was transferred to massive clay pots, called dolia, on raised platforms for storage and sale. (In the slide show these are the two views of huge round pots.) Remember the bones? Those were fished out (sorry for the pun) and ground up in the mortars to make fertilizer or as an amendment to animal feed. An intricate series of stone gutters carried whatever was left off after washing between batches, likely flowing into the local waterways to become nutrients. A true zero waste fermentation operation and likely ran for hundreds of years judging by the layers of flooring tiles that reflect many renovations of the factory.

Now that you know more if you are thinking you are leaning toward the gross camp don’t beat yourself up about it. People have had strong opinions about garum for at least the last 2,000 years. Pliny the Elder, a fellow author described it as “that secretion of putrefying matter” while his contemporary Seneca piled on the garum hate train to ask “Do you not realize that garum sociorum, that expensive bloody mass of decaying fish, consumes the stomach with its salted putrefaction?” Not exactly inviting is it? One of the biggest challenges for some isn’t so much how it’s made but the smell. Make it outside in a shed, on a balcony, or any place that your loved ones (and neighbors) won’t be offended. Also, if you are making a traditional garum with all the animal including the head and organs make sure its fresh. Believe it or not starting out with fish that doesn’t already smell fishy is helpful. This is not a place to decide to use the fish too far gone to eat otherwise. If you know that you want to make an amino sauce, or modern garum you can replace the fish gut microbes and enzymes altogether by bringing in a new team. Sweet floral smelling Koji, aspergillus oryzae, which you can read about all about in our book Miso, Tempeh, Natto and other Tasty Ferments can offer its enzyme superpowers to break down proteins in similar ways. For these modern garums koji is used with a concentrated salt brine and protein.

If you want to explore the world of modern garum you can get started here with this class to make Bone Marrow Garum taught by Meredith Leigh. To read more about fish sauce head to this article.