Our collective stereotype for sauerkraut production comes from a different time and place—giant wood barrels or huge heavy crocks lining the edge of root cellars, that sour-krauty, pickled fragrance permeating the cool dark air. This mental image of what it means to make sauerkraut, while romantic in its self-sufficient, simpler time, homsestead-y way, is not how most home ferments are made. Most people do not want a committed relationship with five gallons of “sauering” cabbage.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Whatever the reason—a small kitchen, a small refrigerator, single or the single fermentation fan in the family, or simply the fun of experimentation and the desire to have a rotating variety of fermented salads in the refrigerator—small is beautiful.

And small requires certain considerations. Let’s start with the large crock of vegetables tucked away to ferment for three weeks—there is mass. This mass of the cabbage bulk helps keeps the weighted ferment under the brine.

This isn’t how it is for small and tiny batches. They will need more baby-sitting. However, with a few management strategies your pint-sized ferment will work, it will be fairly easy and it will turnout delicious.

Keeping track of your brine

Because your ferment is small, it stands to reason you have less brine—remember this salty liquid is your kraut’s anaerobic armor. And keeping this brine in the ferment where it belongs will require a bit more attention while your ferment is curing. Often you will find yourself needing to press gently on your weight everyday. This will release the carbon dioxide bubbles that build up and bring the brine back into the ferment.

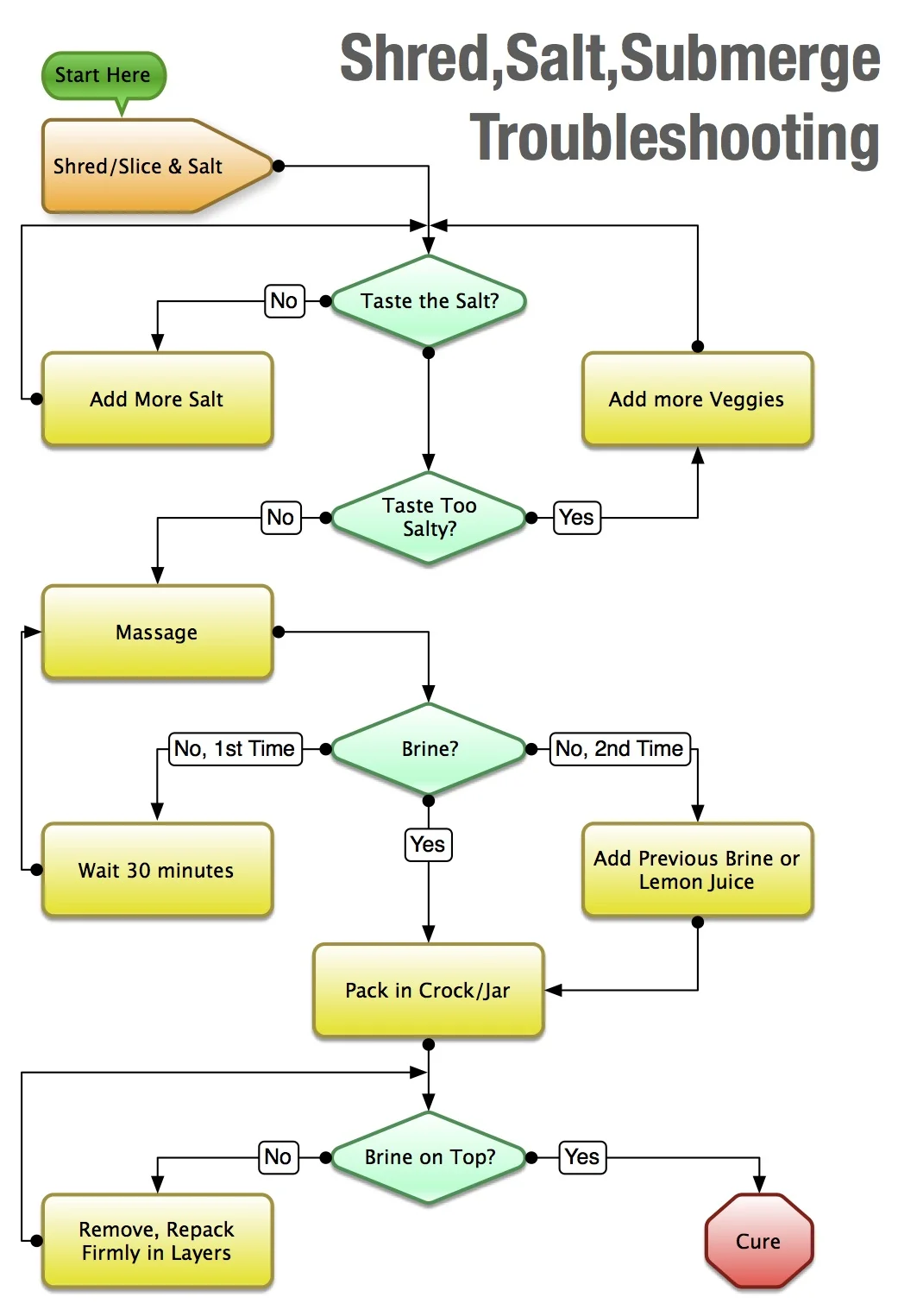

Submerging in brine: Conquers Evil Every time! This simple chant is all you need to remember to keep your vegetable ferments safe to eat. The rules for sauerkraut, kimchi and pickles apply to pastes, relishes, and other fermented condiments. To avoid a “krautastrophe” keep those veggies under the brine. Some of these condiments, like herbal ferments, have much less brine, but there is still enough. Other condiments like salsas or pepper pastes have so much brine that it is hard to keep the veggies from floating to the surface. In either case it is just a matter of managing the brine.

The other challenge is simply weighing down the ferment. Small ferments require small vessels and usually this means the time honored mason jar. (We won’t talk about how many of these jars we own.) So you have salted and pressed your veggies tightly in the jar and you have left about 2 inches of headspace for the brine to expand (but not pour out) as fermentation happens. Now it is time to make sure they stay that way. There are many strategies and many creative folks that have made air-lock lids for jars.

The water-filled ziplock bag is a common method (explained in this previous recipe post) but about a year ago I discovered an alternative to plastic. Stoneware followers made for jars—whole (pictured for wide mouth jars) or split “stones" (for regular mouth jars). Josh Ratza has brought function and art together with the followers he designed for mason jars. Another potter with a unique weighting system is Mikael Kirkman.

Downsizing your recipes

We have found that to keep enough space for the follower, weight and brine it is best not to fill the jar to the shoulder. These weights are a guide to downsizing your ferment recipes and will keep your ferment in a good place. (Josh also includes a few small-size recipes if you buy his followers.) The salt quantities are 1.5 % of veggie weight, some people like a little more. A good rule of thumb is to taste it. You should be able to taste the salt. It should be pleasant and salty, but not briny like the ocean.

For a pint jar :: Use 3/4 pound of vegetables and 5 grams (or ½ teaspoon) salt.

For a quart jar :: Use 1 1/2pounds of vegetables and 10 grams (or 1 teaspoon) salt.