The morning after...nettle leaves soaking in a brine bath overnight—ready to become kimchi.

Living as we do on land at the edge of wilderness, has infused a much closer relationship to the rhythms of the year and subtleties of each individual season. This year, for example, our landscape donned the growth of spring a full month earlier. An important early harvest is the wild nettles that grow in a patch along the creek that runs through our property. Nettle kraut is a standard favorite and it is easy to stick to what I know we love. This year I knew it was time to do something different. On a bright morning Christopher and I headed to the creek with snips, a basket, each wearing long sleeves and good gloves.

I find harvesting nettles thrilling (maybe we’ve lived out here too long); on this day there was extra excitement. As we walked through the thicket of young cedars we happened upon two freshly killed wild turkeys; one was half-eaten, the other was still warm. It was the middle of the day and we wondered what predator we might have scared off—likely a coyote. However, we do live in cougar country and when we got to the nettle bed there was a trampled down area that looked as if something of significant size had been bedded down there. There was an unmistakable odor of cat and suddenly the nettle patch seemed much less benign. As I cut nettles, Christopher surveyed the trees towering over us for a large kitty. I doubt there was a cougar anywhere near, but once our minds imagined there might be, the activity became extreme foraging.

I decided to make a pure nettle ferment and a kimchi-style ferment (and a nettle kraut just in case). We were pleased with the results of both new ferments.

Nettle Kimchi

Yield: About 1 pint

Nettle kimchi is delicious in the magic pungency that is created by the combination of garlic, ginger and chiles, and yet the nettles hold their own. This recipe requires a little advanced thinking as the nettles are soaked overnight. Nettles grow in the early spring. If you are gardener and have a patch of garlic greens add them to the mixture. And remember to use your glove working with the nettles; they still can sting after sitting at room temperature in salt water for 10 hours.

About ½ pound of nettles, the first 2 – 3 rows of leaves still attached to stems

Soaking brine

½ cup salt

2 quarts unchlorinated water

Kimchi mixture

4 green onions, sliced crosswise in ½ inch pieces

1 tablespoon fresh ginger, ground or minced

3–4 cloves garlic

1–2 tablespoons chile flakes or gochugaru powder

Note: As always, adjust the spiciness to your palate. Also the gochugaru is not as hot at the chile flakes and may require more for desired heat.

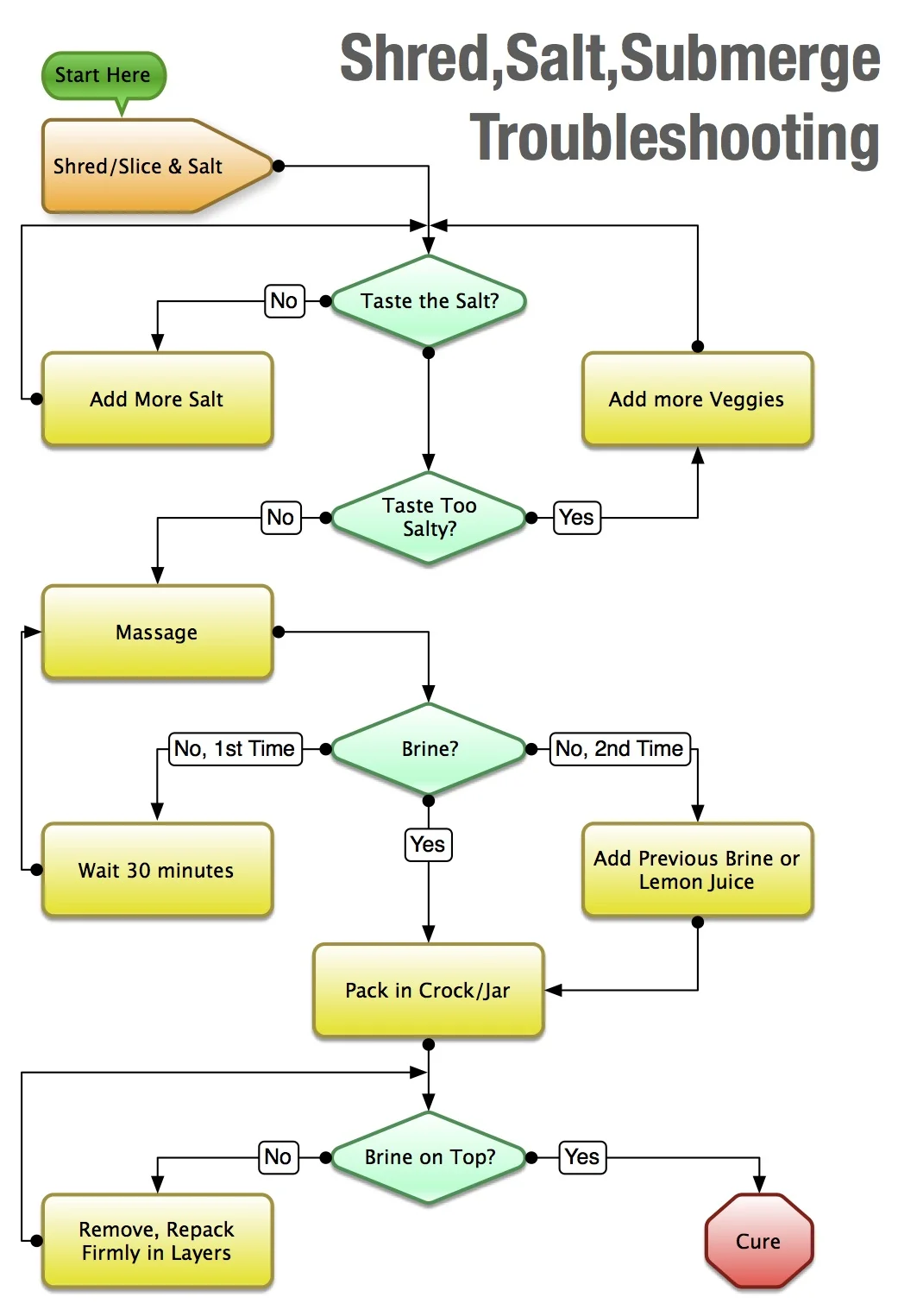

In a crock or a large bowl, combine the brine ingredients and stir to dissolve. Rinse the nettles in cold water then immerse in the brine solution. Use a plate as a weight to keep the veggies submerged. Set aside, at room temperature for 6–8 hours.

Using a colander set over a large bowl, drain the nettles reserving the liquid. Combine the ingredients of the kimchi mixture, blending thoroughly. Set aside. The nettles will clump together. Take this whole clump and roll it up to cut crosswise into 1 – 2 inch pieces and put it in a large bowl. Massage in the kimchi mixture.

Follow the instructions for the type of fermentation vessel you are using. If using the simple jar method select a mason jar with a tight fitting lid that is sized appropriately to the amount of mash. Place the mash inside the jar leaving about an inch of airspace. Add reserved brine as needed to make sure the ferment is juicy and veggies stay submerged. Tighten lid. Set aside, somewhere nearby and out of direct sunlight, in cool spot, for 10 – 14 days.

Check daily to make sure there aren’t CO2 bubbles developing and that the vegetables are submerged; simply press down as needed. If using a plain jar, burp once a day or more often if you see pressure under the lid. Using a utensil, test the kimchi on day 10. You will know it is ready when the flavors have mingled and the pungency is pleasantly fused with acidic tones. The red color will have gotten deeper while the green of the nettle leaf turns a translucent brown khaki green color.

You can let this sit another week in the refrigerator with the lid on to allow the flavors to continue to develop. This will store in the refrigerator for 8 – 12 months.